By Hannah Čulík-Baird.

The Classics and Social Justice group had a productive time at the SCS in Boston this year. Even though the Bomb Cyclone made it difficult for many to get to Boston, we nonetheless had a packed house for our open meeting on the afternoon of Thursday January 4th 2018. Thanks to Lindsey A. Mazurek, we can share the notes from that meeting with you — see the end of this blog post.

On Friday 5th January, we kicked off the meeting with an 8am panel organized by Jessica Wright (USC) and Amit Shilo (UC Santa Barbara). Elina Salminen (U of Michigan) began the panel with her paper, “At Intersections: Teaching about Power and Powerlessness in the Ancient World.” Salminen spoke about how she uses Community-Based Learning (CBL) in her pedagogy, describing a class on issues of equality in the ancient and modern worlds. Salminen had created this class with an audience in mind of students who couldn’t see how the ancient world connected to issues in their own lives. Community-Based Learning is any kind of learning that takes lessons outside of the traditional campus environment, through volunteering, organizing etc. One of the issues with CBL, according to Salminen, is that it requires greater planning up front to make room for both scholarly content and the practice of community work. Salminen also noted that the students who were attracted to this class on ancient and modern social justice were generally not Classics majors, the majority of them were women, and many of them identified as people of colour. Classics classes, Salminen said, which include this kind of diverse material and practice attract a more diverse selection of students who therefore end up taking a Classics class as part of their humanities requirement. One of the themes which consistently reoccurred in Salminen’s experience of teaching in this way was the fact that discussing modern problems of social justice alongside ancient texts allowed students to see more in the ancient material. Students learning about human trafficking in Michigan today, Salminen said, really changed how they viewed Aristotle’s statements about ancient slavery. Salminen included a student testimonial on her handout, which read:

“I feel like learning about slavery in ancient Greece is such a separate topic for me because it feels just like history of something that just ‘happened’ and was a ‘product of its time’. When I read Aristotle, these are the excuses I personally give him for his views on slavery. However, is this what future generations will say about our huge human trafficking problem nowadays? That we didn’t know better and are simply the product of our times?”

Casey C. Moore (Ridge View High School) skyped into the SCS panel session to give her paper, “Engaging Minority Students: Modifying Pedagogical Practice for Social Justice.” Moore began by noting that even though she teaches in an area that has a large population of people of colour, Latin and Greek language classes remain majority white. Most teachers, Moore said, are far removed from the areas where their minority students come from, both psychologically and geographically, and must make an effort to speak to their students’ context. Invoking bell hooks’ Teaching to Transgress, Moore noted that education is about freedom. Educators at all levels see educations as mastery of curricular content, but best the teaching has a student leave class having had the experience connect to their personal life. Moore has students write a weekly journal entry which can have anything to do with what the students are learning in class. The most valuable aspect of this, Moore said, was that it gave her a chance to establish a personal relationship with the students through their writing.

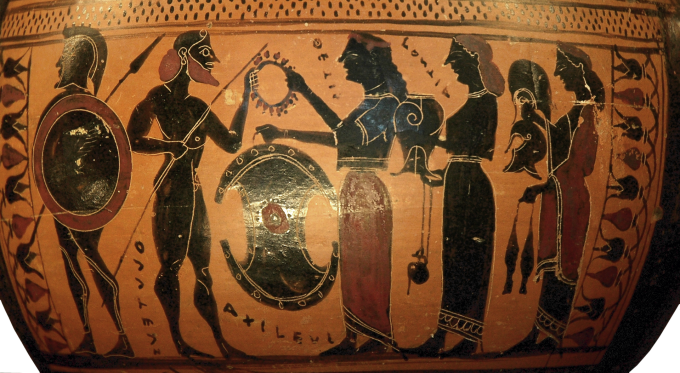

Rodrigo Verano (Universidad Autónoma de Madrid) gave the third paper at the panel, “Reading Homer in and outside the Bars: An Educational Project in Post-Conflict Colombia.” Verano began by noting that an issue with Homer and other classical texts is that students, already familiar with the literature in some way, tend to skim read the text, bringing out the things they were already invested in, not new ideas. Colombia right now, Verano said, is going through a moment where it is transitioning from war to peace. In such a context, the Odyssey can be read in a new light. Verano showed the audience an image of Alex Sastoque’s Metamorphosis or La pala de la paz (Museo Nacional de Ejército, Bogotá, Colombia), saying that this image seems to emblematize how Colombia faces the classical.

With this in mind, Verano brought together university students and the incarcerated to meet and read Homer in post-conflict Colombia. In a piece written by Verano for the Universidad de los Andes, Verano wrote that the discussion focused on issues of justice, especially in the context of the process of seeking peace after conflict. Verano has put together a volume on this work with contributions from seven university students and one inmate, A Ítaca desde el Guaviare. Mirando el posconflicto colombiano desde los poemas de Homero. One of the issues that came out of the Q + A after this paper was the different ways in which the incarcerated engage in writing. Those in the audience who had also worked with the incarcerated noted that in some cases, inmates did not want to write; in others, the prison wouldn’t let written material leave the facility. A theme that wove its way throughout the panel is that social justice work is not the same everywhere: it has to happen where you are, with the resources and circumstances that are available.

Molly Harris (University of Wisconsin – Madison) was the fourth speaker at the panel, with her paper, “The Warrior Book Club: Advancing Social Justice for Veterans through Collaboration.” The Warrior Book Club began in 2016 at the University of Wisconsin – Madison as a discussion of war literature, classical and otherwise. Harris gave an extensive list of modern works which deal with working through issues of modern warfare through ancient accounts: Jonathan Shay’s Achilles in Vietnam (1994), Odysseus in America (2002), Lawrence Tritle’s From Melos to My Lai, Peter Meineck and David Konstan’s Combat Trauma and the Ancient Greeks (2014), Victor Caston and Weineck Silke-Maria’s Our Ancient Wars (2016), Ancient Greeks/Modern Lives, Theater of War, Roberta Stewart’s reading group. Asked after the panel whether the group plans to read poetry, Harris responded: yes, women’s poetry — Scars Upon My Heart, written by women warriors of the first World War; Powder, written by women in the ranks from Vietnam to Iraq. I have written elsewhere about how Harris’ presentation of a bibliography was an invitation for anyone interested to do this kind of work themselves. Harris noted that one of the early issues with the reading group is the status of the classical texts themselves: readers tend to think that the texts have been assigned (Odyssey, etc.) because we’re supposed to find the “answers” there. This means that the facilitators of such work need to make it clear that discussion and dialogue is the main goal, not to arrive at a specific conclusion (much like Moore’s invocation of bell hooks, who encourages teachers to have students stop seeing them as the center of all authority/knowledge production). Harris also brought up an important point when she described her own contact with the media as part of this project. Scholars often don’t know how to speak with journalists or the public at large. Being public facing isn’t easy, but it is important. In the Warrior Book Club, Harris said, the topic of translation was of great interest: obscenities in Lysistrata spoke to a veteran who remembered how his Iraqi translator deal with obscene graffiti.

The last speaker on the panel was Amy Pistone (Notre Dame), who skyped in to give her paper, “First Do No Harm: Responsible Outreach and Community Engagement.” Before appearing on the screen, she tweeted the handout to her paper:

Pistone began by laying out the best practices of social justice work, emphasizing the fact the classicists engaged in this kind of work should have a clear vision of precisely what their role is — why are you doing this particular work with this particular community? Where does Classics belong in this dialogue? Pistone reiterated a much discussed issue, that of the language of “outreach”, which suggests “in” groups and “out” groups.” When asked in the Q + A what term she prefers, Pistone said that she like the words “community” and “connections.” Pistone noted that it is not enough to say that the world needs Classics. Like Moore, Pistone made the connection between education and liberation, this time invoking Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed and ideas of critical pedagogy as concerned with “critical consciousness”, liberation as a transformational praxis. Pistone also noted that we need to rethink classical exceptionalism, invoking Rebecca Kennedy. Pistone also recommended Christopher Emdin’s For White Folks Who Teach in the Hood…and the Rest of Y’all too, noting that “white folks” is distinct from the race of the teacher, but rather describes a eurocentric pedagogy which focuses on teaching hierarchies.

See below the notes from our open meeting on Thursday January 4th, compiled by Lindsey A. Mazurek. A pdf version is available here.

The CFP for our panel at next year’s SCS in San Diego (2019) is already available. Read it here and consider sending an abstract.